Do you remember the first time you heard it?

You’d just moved halfway across the country and were hearing everyone in your partner’s graduate program for the first time.

Do you remember the young Serbian soprano—she would soon leave for a young-artist position at the Royal Opera House—her voice radiating confidence, optimism, and physical pleasure as it ascended to the high A-flat?

Do you remember thinking: how have I never heard this before?

•••••••

Do you remember being told Wolf only set texts other composers had set when he found the settings lacking? Did he know Beethoven’s, Schubert’s, Fanny Mendelssohn’s, Schumann’s, and Liszt’s (three) settings? Can you imagine knowing some or all of these, yet desiring to set Mignon’s words again?

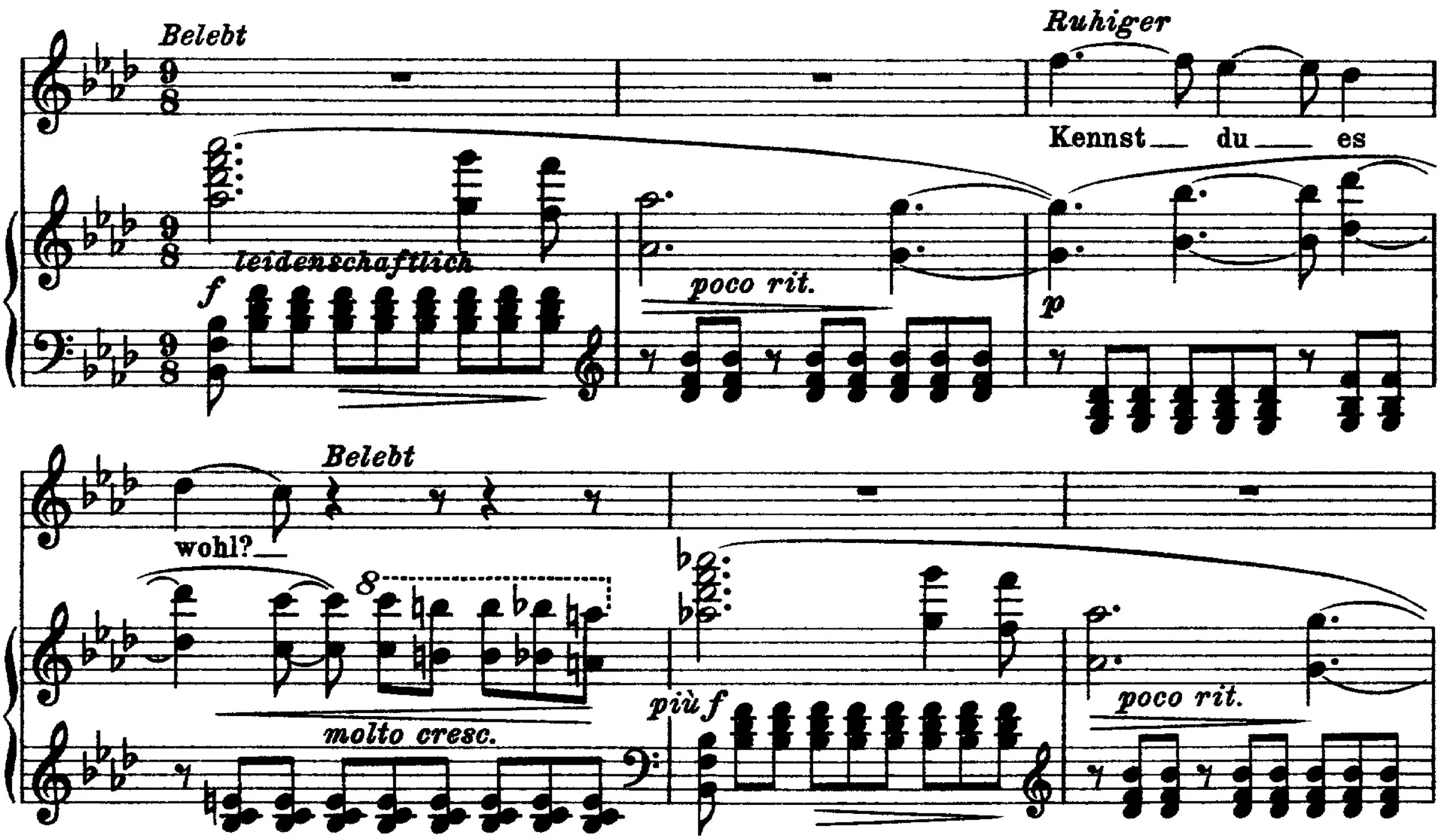

Do you feel how the tonality gradually brightens—moving smoothly from G-flat major through E-flat major to C major? Do you sense the gentle wind and warm blue skies of Mignon’s vision in the off-beat piano pulses? Is there something foreboding in this brief idyll—the upward leap at the vocal phrase’s end a question mark punctuating the preceding serenity, tinging the long, graceful phrase with strain as the singer’s breath runs out? Do you sense that as the piano falls chromatically from the voice’s final C, an alchemical transformation occurs—what had seemed like repose becomes unstable, pulling us toward a new tonality?

Hugo Wolf, Goethe-Lieder, “Mignon: Kennst du das Land,” mm. 17-20: Something foreboding in this moment of stillness?

[source: IMSLP, C.F. Peters, public domain]

Do you agree the next moment is a miracle: perhaps the most gut-wrenching ugly-cry in all of German Lieder?

Do you feel that this seven-note chord with a two-octave absence at its center hits harder than should be possible? Do you feel how the harmony breaks the conventional rules, stepping backward from the dominant to the subdominant? How this chord’s added seventh—the high A-flat in the piano’s right hand—gives the expected melodic resolution, while the bass note—the low B-flat—shifts the ground underneath?

Do you feel that the ugly-cry is simultaneously a shocking interruption and inevitable continuation? That the register, tempo, meter, and texture all shift, yet the vocal melody seems to connect across these disjunctions? Do you feel that the repeated, offbeat chords in the left hand give the music a breathless urgency? (A detail: the pattern of repeated attacks in the piano’s left hand in the first statement of this four-bar phrase—8, 2, 5, 5, 2, 8—Wolf modifies in the second phrase to 8, 2, 5, 2, 5, 5, 2.)

Do you agree that the offbeats in the piano and syncopations in the voice cause the beat to seemingly move around the measure? That the rhythm is much more unstable than it appears on the page? Do you feel the tension of the vocal entrance in measure 23, where the F on “Kennst” rubs against the piano’s sustained G, a second above? Do you sense the music’s written-out rubato: how the length of the vocal line’s notes decreases from four 8ths, to three, to two, gradually accelerating toward the D-flat on the downbeat of measure 24? And do you feel how the vocal and piano parts converge here to emphasize the sobbing 9-8 suspension gesture—yet another subverted convention, in that the suspension presupposes a contextualizing bass note that isn’t there? And how this lean against nothing—out into thin air—expresses the vertigo of existential dread?

Do you now realize that the bass register vanishes entirely after the initial stab of the seven-note chord? How the wound this stab opens up only just begins to cover over before being ripped open again by the chromatic descending octaves in the piano’s right hand in measure 24? How the repeated B in this sobbing gesture is a means to fit something fundamentally fluid and vocal into the discrete intervals of the equal-tempered keyboard?

Hugo Wolf, Goethe-Lieder, “Mignon: Kennst du das Land,” mm. 21-26: the most gut-wrenching ugly-cry in all of German Lieder?

Do you recognize, after this heart-pang, the tragic wistfulness of the perfunctory cadential formula that follows—a closing of the heart, a forced return to moderation and rationality after a moment of raw vulnerability? Do you feel how the triplet rhythm from the preceding calamity alters the opening music’s character upon its return, giving the formerly placid accompaniment a new momentum, but maybe also a trace of anxiety?

mm. 35-38: the tragic wistfulness of the perfunctory cadential formula

Do you feel the second time the ugly-cry of “Kennst du” occurs, it runs the risk of becoming routine? Yet, the third time—following the tremolo passage in F-sharp minor illustrating mountain caves and dragons—it’s somehow even more devastating than it was the first time? How, at long last, the music cadences in F, which was implied by the “Kennst du” music both times, but never occurred? And how the confusion of the dramatic shift down from F-sharp minor to F minor only increases the radiance of the unexpected resolution of that long-unresolved dominant to F major? But how the gravitational tractor-beam of “Kennst du” won’t allow this fleeting radiance to last, and pulls the music back down once again into darkness?

mm. 92-97: the gravitational tractor-beam of “Kennst du” pulls the music back down once again

Do you know it well?

![Hugo Wolf, Goethe-Lieder, “Mignon: Kennst du das Land,” mm. 17-20: Something foreboding in this moment of stillness? [source: IMSLP, C.F. Peters, public domain]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/562f8b0ae4b0726ad490b26a/1573844055681-W9CYQ00A0NZROACEXX26/kennst1.jpg)